It’s accepted wisdom in the writing community that it’s important to “show” and not “tell” your reader what’s going on. Notice the differences below:

Telling: “Freddie was nervous about meeting his boss for the first time.”

Showing: “Freddie’s hands trembled as he smoothed his tie, cautiously sipping air as he glanced at his watch.”

Clearly, the second example is not only more visual, but more interesting.

Showing also requires the reader to do more work, forcing them to participate more in the activity of reading.

When people refer to writing as being “smart” I think that’s what they mean. When they are shown, and not told, they feel smart because they have to do a little more work.

In other words, the writing isn’t necessarily smart — they are.

But writing for the screen is different.

Viewers are faced with endless distractions while watching television or movies. Today, it’s common to watch the screen and scroll your phone at the same time. If writers simply “show” there’s a good chance that the audience is going to miss it.

So what’s the solution?

“Show” THEN “tell.”

Do both!

Doing this has helped make me a successful screenwriter, and I use the same technique when writing books.

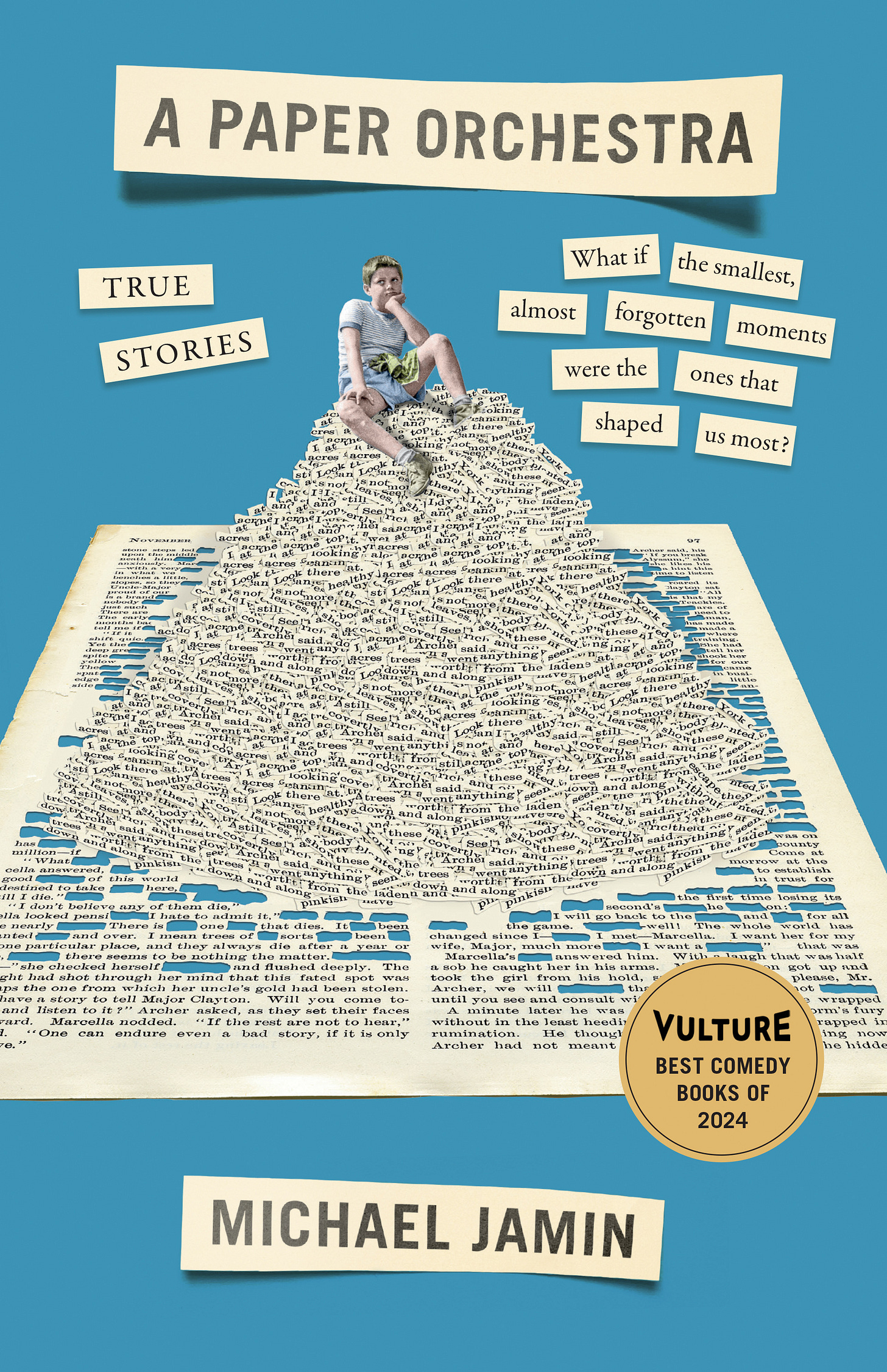

Here’s a passage from my collection of short stories, A Paper Orchestra.

In it, my father is disappointed with how wimpy I was as a kid, so he forces me to participate in a judo competition, hoping it will toughen me up. But instead, he watches in horror as I get beaten up. The following passage takes place shortly afterwords.

My father and I sat in silence during the ride home. I felt small sitting in the front of his car, and with each bump in the road, I sank further and further into the seat, hoping to eventually disappear.

“You did great out there,” he finally said. “Really great.”

He said it with a softness in his voice while not quite looking at me, so I couldn’t see the lie. I turned my head toward the window, trying to hide my face as I wondered how soon it would be before I had to get the shit kicked out me again.

“I think we’ve had enough judo for awhile, don’t you think? he suggested.

Maybe in that moment, my father realized that he had been mistaken, that all his fond memories of being dehumanized in the army weren’t meant to build character. They were meant to destroy it, turn men into something they weren’t so that they would follow orders instead of their hearts.

Look how this scene unfolds. I show my father feeling remorseful for turning me into something I’m not. He speaks with a “softness in his voice, while not quite looking at me…”

Then, in the last paragraph, I tell the reader what he’s feeling.

“Maybe in that moment, my father realized that he had been mistaken…”

Show, then tell.

I do this not just at the end of every story, but all throughout. It’s how I, as the author, check in with the reader to make sure they’re still with me.

Good writing takes the reader on a journey.

“Telling” is how I hold their hand while taking them on this journey.

“Showing” is how I let go of their hand for a moment, allowing them to walk on their own.

If you’re interested in improving as a writer, I recommend reading A Paper Orchestra with a highlighter.

Read the book once for enjoyment. Then read it again. This time, highlight the passages where I “show.” And using a different color, highlight the passages where I “tell.”

Seeing this visually, you’ll quickly discover a pattern of how and when I use “show vs. tell.” You can apply a similar pattern to your work, not only entertaining your readers but taking them on a journey.

Show, then tell.